I enjoy working as a master of ceremonies. Whether the funeral is grand or modest, and regardless of the status of the deceased or their family, every funeral is a stage for witnessing the spectrum of life and social ideologies. Each farewell reveals different expressions of grief—some heart-wrenching, others stoic. As a host, my ability to comfort the bereaved is limited, but I firmly believe that simply having someone present for support during this final journey is profoundly meaningful. This is what gives my role its sense of purpose.

At the same time, traditional Chinese funerals are often unsettling for me as a woman. I am constantly reminded of the deeply ingrained gender biases that permeate the rituals and customs.

In company displays, the name of a deceased married woman is often shown as “Madam [Husband’s Surname].” As the master of ceremonies, I often have to search the small ancestral tablet to find her full name. As a woman who lived decades as an individual and contributed so much to her family and society, why is she reduced at her death to being merely an extension of her husband who doesn’t even have the privilege of having her full name properly displayed?

I once hosted a funeral where the deceased’s daughter was the primary organizer. When it was time to pay final respects, the ritual guide called for the son first. As the daughter stepped forward next, the ritual guide said, “Daughters-in-law first,” and she instinctively shrank back, wearing an expression as if she done something wrong. After the daughter-in-law and the eldest grandson had gone, it was finally her turn. Whether she accepted this hierarchy out of respect for the occasion and tradition or simply endured it for her parents’ sake, her compliance pained me as a fellow woman. This incident is not isolated but part of a broader, systemic issue.

In these customs, a son’s spouse and children are viewed as “family”; while a daughter’s spouse and children are regarded as “outsiders.” Daughters wear mourning badges with a red mark affixed to it while the red worn by the sons-in-law will be even more explicit. This red, meant as a sign of respect, is often a symbolic wound in the hearts of daughters who feel excluded. Behind this euphemistically named “ritual” lies the patriarchal ideology of favouring sons over daughters and sense gender inequality.

During ceremonial offerings, the husband’s family takes precedence over the deceased woman’s biological relatives. Blood relations and direct family members are seen as inferior in comparison to those of the husband’s. Only sons are allowed to hold the ancestral tablet and divide the inheritance, while married daughters are often barred from freely worshipping their parents to avoid “diminishing” the blessings meant for the sons.

Some families today actively request less rigid adherence to these traditions, and funeral service providers adapt accordingly. Yet, the traditional framework remains the default. Defaults reflect collective societal consciousness. As service providers, why shouldn’t we take the lead in normalizing gender-equal practices as the default, while still accommodating families who wish to follow traditional norms?

Someone once told me, “Gender equality doesn’t need to be demonstrated through a funeral; women already have freedom and equality elsewhere.” To this I say, if equality cannot even exist in ceremonial formalities, how can we expect it to manifest in the broader world? If a woman cannot receive respect even in death, how can we believe she will be respected in life—in her family, workplace, or society?

Even today, among my well-educated and financially independent female friends, many still face parents who insist only sons should inherit family property. The hurt does not stem from the lack of inheritance but from the apparent disregard for the love and care daughters have shown. Are we still pretending that gender inequality in Chinese funeral customs is “just symbolic”?

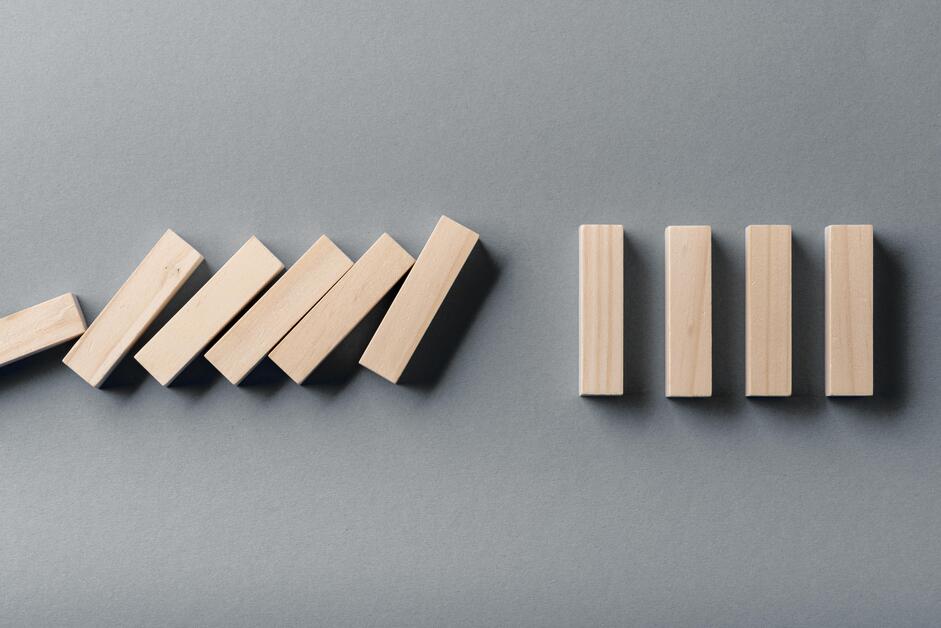

Looking back, women’s social status has certainly progressed over the past century but none of these improvements came easy. Every gain was the result of struggles and hard fought battles by many generations.

It’s hard to imagine today that when the Olympics first began, women were not allowed to participate or even watch. It wasn’t until 1924 that women were officially permitted to compete. Even then, as late as 1967, the Boston Marathon barred women from participating. Kathrine Switzer registered under a male pseudonym to protest, only to be violently harassed during the race. It wasn’t until the Tokyo 2020 Olympics that female athletes finally represented nearly half of all participants.

Does gender equality matter to business? According to a McKinsey & Company report, closing the gender gap could add $12–28 trillion to global GDP. Gender equality is also one of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, signed by 193 countries, including Malaysia.

Yet, the 2020 Global Gender Gap Report ranks Malaysia 104th among 149 countries, a drop from previous years. In economic participation and opportunity, Malaysia ranks the lowest among ASEAN countries. As a leading funeral service provider committed to humanistic values, shouldn’t we actively advocate for gender equality, knowing it benefits both the economy and national reputation?

The report also reveals that the pandemic widened the gender gap, pushing the timeline for global gender equality from 99 years to 136 years. How many more unexpected crises will further delay this progress?

Do we really have to wait another 136 years for women to receive respect in traditional Chinese funeral rituals?

Written by Ng Ai Ling on International Women’s Day, 2022

Ritual and Culture Management Department

Exploring the influence and development of Chinese culture on Malaysian society, with a focus on the origins of funeral traditions. This includes drawing insights from ancient cultural practices and their evolution, thereby enriching the growth, cultivation, and expansion of Nirvana’s funeral services.

Author profile

Ng Ai Ling of Nirvana Care’s Ritual and Culture Management Department, has a Master’s degree in Chinese Language and Literature from Taiwan’s National Dong Hwa University, with extensive experience in writing and research. She is a regular newspaper columnist and a long-time contributor to online platforms in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Double Spring and Leap Month

What are “Double Spring” and “Leap Month”? A Double Spring Year refers to a year containing two “Beginning of Spring (Lichun)” solar terms. In the 24 Solar Terms system, Beginning of Spring symbolises the awakening of yang energy and nature’s rebirth – the beginning of annual vitality. Two Beginning of Spring occurrences signify double yang energy and the return of spring’s blessings, making it extremely auspicious.

A Leap Month Year occurs due to……

Stars in the Night Sky

we will become a star in the sky, becoming one among a sea of twinkling lights. We can always see our loved ones and friends in the night sky, so we won’t be alone

Worship offerings: Preserving tradition and keeping up with the times

there is a traditional proverb for worship, that it is hoped that people should drink water and think of the source, and to pay careful attention to one’s parents’ funerary rites and to worship one’s ancestors. The children and descendants must remember that they owe it to the sacrifices of their ancestors that they get to enjoy the shade of the great trees and the fruits of their labour!

So this is what my social media accounts will look like after I’m gone!

So this is what my social media accounts will look like after I’m gone! Although there are still some who will avoid talking about death, people are beginning to accept the inevitable and face it positively and pre-plan with changing times. However in modern society,...

Nirvana’s Golden Harvest Reward: An excellent mutual benefit for customers

A free gift given with purchases of specific Nirvana products, the innovative reward programme allows customers to enjoy an estimated 4-times reward of the purchase price in a period of 30 years – with zero risk and zero investment capital – creating a win-win outcome for everyone.

Maintenance trust funds for memorial parks: Why is it important for customers?

Maintenance trust funds for memorial parks: Why is it important for customers?

The Final Portrait

Many people tend to think they don’t need to have their pictures taken or they dislike the notion because they are too old. Later however, when the time comes to prepare for the funeral, there simply isn’t a suitable or presentable photo that can be used as a funeral portrait.

RHYME OF LIFE: A PRICELESS TREASURE OF LOVE

“The goal isn’t to live forever, the goal is to create something that will.”

Nirvana Center Kuala Lumpur built their unique columbarium that is touted to be unlike any other found in Malaysia – the Rhyme of Life, embodying American journalist and novelist Chuck Palahniuk’s quote above.

Why are funerals needed?

Every ritual at a funeral is a way to accept the fact that we have lost a loved one, and the loss of a loved one is an unavoidable life experience for everyone and it is also a process.

PRE-PLANNING THE FUTURE AS AN ACT OF LOVE

In some cultures, death is a taboo topic.

What’s more, to talk about death and money in the same conversation would raise suspicion of greed and distrust.