The Funerary Ritual of Liberating the Deceased and Comforting the Bereaved

In traditional Chinese funerals, it’s common to see a ritual called “Breaking Hell” (Po Di Yu 破地狱), performed with a range of practices and varying scales, depending on regional and dialect group customs. However, what is its purpose, how is it conducted, and are there any specific requirements?

To begin with, “Breaking Hell” is a Taoist ritual; therefore, it generally isn’t performed in Buddhist funerals. The ritual’s purpose is, as the name suggests, to open the gates of hell and free the deceased trapped within. However, Taoist priests conducting the ritual doesn’t have the power to release souls on their own. Instead, they conduct a ceremonial petition to the Heavenly Lord of Supreme Oneness and Salvation from Misery (Tai Yi Jiu Ku Tian Zun太乙救苦天尊), a deity of compassion, to help in liberating the souls. Although the deity is powerful, he is not omnipotent. Whether a soul can ultimately leave hell depends on the deceased’s own karma and their acceptance of the Heavenly Lord of Supreme Oneness and Salvation from Misery’s teachings, along with sincere repentance for their misdeeds.

In Taoism, “Netherworld” (Yin Jian Di Fu阴间地府, lit. “Yin Realm Underworld Mansion”) and “Hell” (Di Yu地狱, lit. “Underworld Prison”) represent different concepts. In earthly terms, only those who commit severe offenses are sentenced to prison. Similarly, after death, most souls go to the netherworld (realm of the dead), while only those burdened with significant misdeeds enter hell. Therefore, not every deceased person requires this ritual. However, if the family is uncertain about the deceased’s fate, performing the ritual is a way for children to fulfil their final filial duty.

The concept of “Breaking Hell” is similar across different dialect groups, though the specifics vary. Hakka priests, for example, create the form of two dragons out of sand, place eggs and a small paper gate, and eventually lift the gate to symbolize its breaking. In Teochew practices, the ritual is dramatised with scenes from “Mulian Rescues His Mother” (a story with Buddhist origins, reflecting the Taoist-Buddhist syncretism common among the Teochew). One priest plays the role of a jailer, while another plays Mulian; after a performance involving dialogue and combat, Mulian breaks through the paper gate to show the opening of hell. In the Hong Kong-style Cantonese ritual, priests surround a fire with tiles, breaking them one by one to symbolise the breaking of hell’s gates.

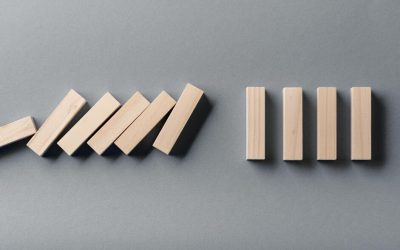

The essence of “Breaking Hell” lies in the realm of intent, not in the literal actions observed during the ritual. However, because people can’t perceive the metaphysical, Taoist priests bring the ritual to life with visual representations, even theatrical elements. Regional variations incorporate local customs, like traditional opera, to provide a compelling experience that assures the family of the ritual’s efficacy.

An effective “Breaking Hell” ritual not only liberates the deceased trapped in hell but also offers solace to the grieving family.

Accumulating Intercalary Months for Longevity — How Many Years Should Be Added After Death?

What is “Accumulating Intercalary Months for Longevity”? Both the Gregorian and Chinese Lunar calendars we use today include the concept of intercalary adjustments, though the concepts differ slightly. The Gregorian calendar is solar-based, having its basis on the time it takes for the Earth to complete its orbit around the sun, which is approximately 365.24 days. The system necessitates adding an extra day in February every four years – making it an intercalary or leap year – to keep sync with the seasons.

Why must tomb-sweeping rites for new tombs be done before Qing Ming Festival?

Many believed “Early Qing Ming” is a special privilege granted by the Lord of the Netherworld to new spirits, allowing them to enjoy the offerings of filial descendants earlier without having to compete with older spirits. Therefore, descendants can perform ancestral worship earlier without waiting for the arrival of Qing Ming Festival. The other reasoning is more rational and practical in nature.

“Numinous Treasure Authorisation to Traverse the Netherworld” — A Passport to the Afterlife

The “Road Pass” is essentially a passport issued by Taoist priests for the deceased, ensuring they can navigate the journey to the afterlife without obstacles. It typically includes the deceased’s basic information, such as their name, dates of birth and death, place of origin, and their address. Originally, the “Road Pass” was meant to be used exclusively during funeral rites. For subsequent ancestral offerings, burning paper effigies and clothes trunks does not require it. However, over time, the “Road Pass” was seemingly adapted to function as a form of “seal” to ensure the offerings reach its intended recipient.

Taking a Step Back at Funerals: A Century-Old Gender Gap

…many still face parents who insist only sons should inherit family property. The hurt does not stem from the lack of inheritance but from the apparent disregard for the love and care daughters have shown. Are we still pretending that gender inequality in Chinese funeral customs is “just symbolic”?

Seven Weeks (Forty-Nine Days): How to Perform the Rituals Correctly

Have you ever heard of the “First Seven and Final Seven Days” after a person passes away, and the belief that there are rituals to be observed for forty-nine days, or that the soul of deceased will return on the seventh day? What are the origins of these beliefs, and how should these rituals be observed after the passing of a family member? What happens if these rituals are not observed?

Are there “taboos” to observe during the mourning period after a funeral?

One of the most common explanations is that “red and white must not clash,” meaning those in mourning should not attend celebratory events to avoid bringing “misfortune” to the hosts. Is this really the case?

Treating the Dead as in Life: Reflecting on the Meaning of Ritual

In the “Doctrine of the Mean” from the Book of Rites, there is a phrase: “Thus they served the dead as they would have served them alive; they served the departed as they would have served them had they been continued among them – the height of filial piety.”